|

As a visual artist, I as interested in exploring what we see and how we see. We don't see objects, rather we see light reflected off objects. The portion of the light we see is made up of discrete photons with wavelengths within the visible spectrum that are caught by four kinds of photoreceptors arrayed in the back of our retinas. Those receptors emit electric signals that are processed by complex circuitry in layers of the retina and sent to many sites in the brain which create our sense of the real world.

Despite amazing modern day research into their workings, the astounding complexity of our visual and neural networks are largely indeciphered. The best source I have is R. W. Rodieck's "The First Steps in Seeing" 1998, Sinauer Associates, Inc. We see the mix of photons in the visible spectrum as white light or separately as colors - low energy/long wavelength red, orange, yellow, green, blue to higher energy/shorter wavelength violet. Supposedly we can distinguish between 1 million different colors, although whoever did that research probably lost count after 1,000. We can’t see photons on either side of the visible spectrum, lower energy infrared photons we feel as heat and higher energy ultraviolet photons that give us sunburns. The water in our eyes filter out most of the ultraviolet ones which would damage our retinas. It seems to me that one starting point of this exploration are the photons that reach our eyes. The word photon was invented in 1926 and is mashup of the Greek word phos = light. Almost all our photons come from the Sun and have a range of energies inversely proportional to their wavelengths. Physicists describe photons as part particle and part wave and have derived complex mathematical formulas linking photons with electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, space, time and gravity. Photons travel at the speed of light (redundant description) and have no mass (also redundant; by definition, particles with mass supposedly cannot travel at the speed of light). Photons also have angular momentum [they spin] and they can be separated by interacting with matter, what we call polarization. My artistic mindset has boiled all this photon stuff into an analogy: Picture the Sun as a giant kettle, spewing out trillions of spinning popcorn kernels called photons. The kernels are all the same size, and travel at the same speed ( duh the speed of light) but they are spinning at different rates and in different orientations. If you have ever played with a child’s top or a gyroscope, you know that the faster they spin the harder it is to move them. So the faster photons spin the more energy they have. I can't find any experimental findings on how fast photons spin, so I am thinking the photon energy/wavelength thing is just a measure of spin speed, longer wavelength photons precessing more than shorter wavelength photons. Apparently the 20 million photo receptors in each eye catch only a tiny portion of the millions photons that pass into our eye every second. More photons with wavelengths within the range of each of the 4 photoreceptors are captured and the brain integrates the totals to discern color and brightness. Most photons pass right thru and are absorbed by a black layer in the back of the retina and removed as heat by the network of blood capillaries and vessels bringing oxygen and nutrients to the eye. I think our photoreceptors not only record photon strikes and the wavelength of many of them as a particular color, but can determine their polarity*, which may be involved in our "holographic" ability to discern three dimensionality. More on that subject in a later post. * Google "Haidinger's brush" and see if you can duplicate Wilhelm Karl von Haidinger's 1844 discovery of our perception polarization of light.

0 Comments

Of the various forms of art, I recommend the still life as the best learning tool. When I started out I first studied the still life paintings of Chardin. I copied paintings by Chardin and Cezanne, among others. 1973 Richard Perry oil on canvas from Chardin composition

The advantages of still life painting are: You can take your time (until the fruit rots). Unlike a landscape you can easily rearrange the composition. I recommend using a lazy Susan so you can spin your objects around to get new views. This allows for randomness - a great tool to progress in art. (I read that one of the Impressionists, it may have been Renoir, painstakingly set up a flower still life in class, only to instruct the class to paint if from the back. "Perspective" in art is the systematic placing of visual information on a flat surface so that nearer objects appear larger than than those farther away. Early perspective painting was concerned with depicting architectural spaces, (see Canaletto's work, above). Much later art derived from photography since the lens projects a perspective image on a flat surface. I think Vermeer was the first to actually apply lens images in painting. If you have any doubts, look at the recent documentary, "Tim's Vermeer". Photographic perspective varies with the focal length of the lens, the longer the focal length, the more the perspective is compressed.

Wikipedia currently states, "Linear perspective is an approximate representation, generally on a flat surface, of an image as it is seen by the eye." This is nonsense. Perspective bears no resemblance to how the eye (and brain) process three dimensional visual information. Also from Wikipedia: perspective (from Latin perspicere 'to see through'). In the early 1970's at the Art Students League I was encouraged to think of perspective by imagining a pane of glass through which to view a subject for drawing or painting, and on which to record the perspective image. No art teacher actually tried this experiment, so I did so in my 7th Street loft. I stretched a sheet of clear plastic at arm's length and tried to draw the interior image of the loft on the plastic using a black marker. I was able to mark a point or two as seen through the plastic, but as soon as I focused on the plastic as opposed to looking through it, the interior image abruptly contracted because my eye refocused to arms length when viewing the marks I had drawn on the plastic. A few more tries also revealed that I could not reproduce the light values or colors of the seen image, since the light falling on the plastic was different that that illuminating the scene. I have since learned much more about our visual system and how different it is than the camera, but suffice it to say the concept of perspective is often antithetical to making art. An artist would do better to draw and paint the most noticeable elements in a scene, which is how the eye takes in information, rather than trying to arrange them in perspective. "When to stop? " can be applied to many moments in life. But I'm focusing now on:

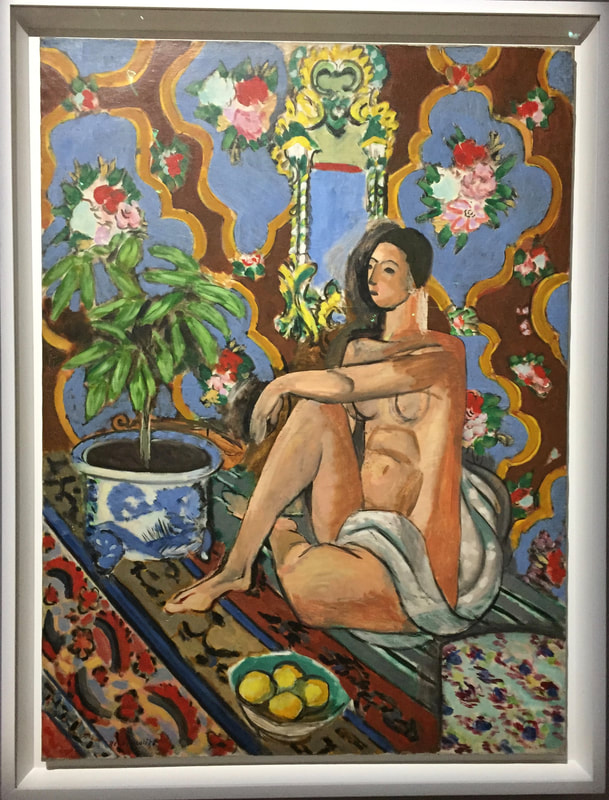

When to stop working on a painting or other piece of art? In other words, When is it finished? The short answer - a work of art is never finished until it leaves the artist's studio and sometimes not even then. I recall reading that the abstract painter Clifford Still was sued by the owner of one of his large canvas paintings. Years after it sold for big money, it was returned, damaged, to Still, rolled up, with a note essentially saying, "Fix it". About a year later Still sent it back. Still had completely painted over the original work. The Judge sided with Still, since the owner didn't specify how to fix it. Sometimes the answer to "When to stop?" is clear: a quick sketch that sings to you, or when you exhaust an overworked piece to further one's knowledge. But often you reach a stage in a work where it seems unified, but the question arises, should I leave it now, or continue on? You can always do more, but recall the late comic Gilda Radner's adage, "There's always something." It may be worth while to reframe the question from, "When to stop?" to "Should I continue?" My advice: 1. Stop work and sleep on it. Your creative brain (right side) has probably reached its limit and has turned things over to the analytic (left side) of your brain which is posing the question. 2. When you get up in the morning to study your work, your right brain will be in control again. If there is somewhere creative to go with that piece, then proceed. If not, sign and date it and start something new. The photo above is of a large Matisse masterpiece at the Pompidou Museum in Paris. Notice the shaded and scuffed area behind the sitter's head. Matisse must have reworked the head many times, but wisely left the resulting background alone when the portrait was complete. Watercolor, Rock Harbor, Orleans, 2019

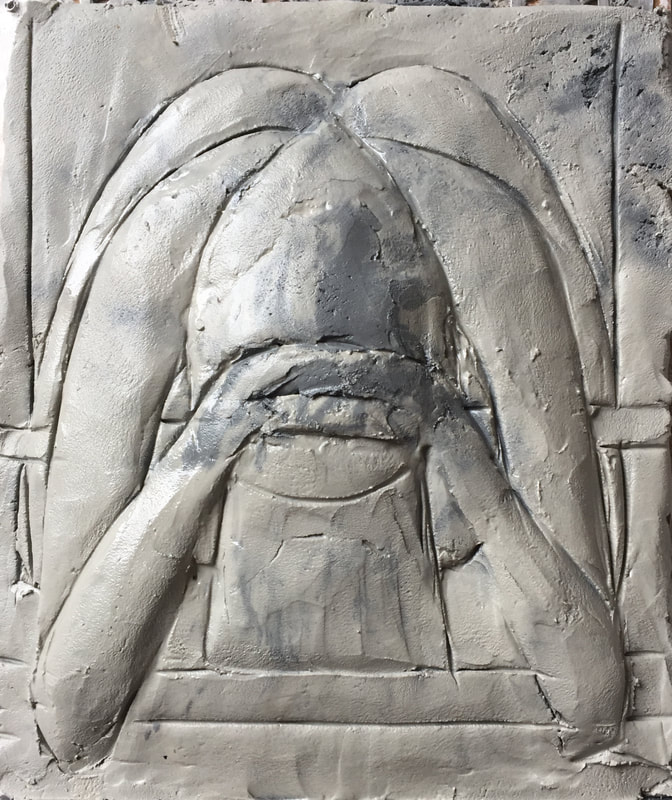

I have struggled with the question everyone is asked at some time or another, "What is your favorite color?" I guess on reflection, mine is the ice blue of a glacier I saw once in Glacier Bay, Alaska. Its novelty makes it my favorite. However, as an artist, I find it best to ditch the word "color". Instead I think about the properties of the colored paints I use. In this sense, painting becomes like cooking, where the particular ingredients and how they can be used and combined, are important, rather than some abstract concept of taste. My favorite blues are the pigments ultramarine blue and cobalt teal, which I use in water colors and acrylics. They usually cover the blue spectrum very well for me. I also use thalo blue which has a slight greenish cast and which also comes in green(er) and a red shade, the latter close to ultramarine. Cobalt blue sometimes makes a good upper sky color. But keep in mind that "color", as we see it, is relative. Blue is the name we give to things we see that absorb all of the visible spectrum except blue wave lengths. But the blue we see depends on how we see it. Blue sky at dusk is a dull blue. But if you are walking outside from an interior lit by artificial light, the sky will appear a bright electric blue, which fades to blue-grey over a few seconds as your visual system readjusts to darker lighting conditions. A blue crayon placed between two orange ones will give a stronger appearance than one placed between two yellow ones because our visual system is recording the wave length differences. with the orange wave length being farther away from blue than yellow. Many of Rothko's paintings comprise wide horizontal bands of diffuse color. To me, they are peaceful and contemplative. What about vertical bands of color? To me, they conjure up action and movement. Perhaps there is a physiological = psychological basis for this difference. When we scan up and down with our eyes we are usually taking in information from a object at rest. When we scan sideways we are often following a moving object or words on a page. Can the same be said of poetry which scans vertically compared to non poetic text? Reliefs below: 2016-2 Bayview #1 and 2015-30 Nickerson #1

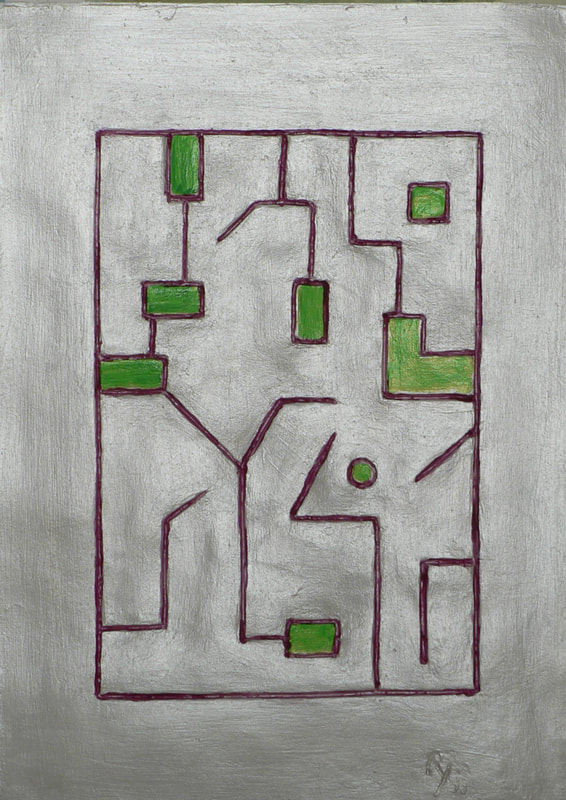

A-I machines learn through repetition. When a solution is found it may be difficult to explain how the result was reached or how it can be duplicated by others. How is that different from an artistic creation? Below: 2008-11 relief "Does not Compute"

When you reach a point where you are stuck, complicate your life or art, then simplify by keeping what is most important..

|

AuthorRichard Perry is an artist in Brewster, Massachusetts Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed